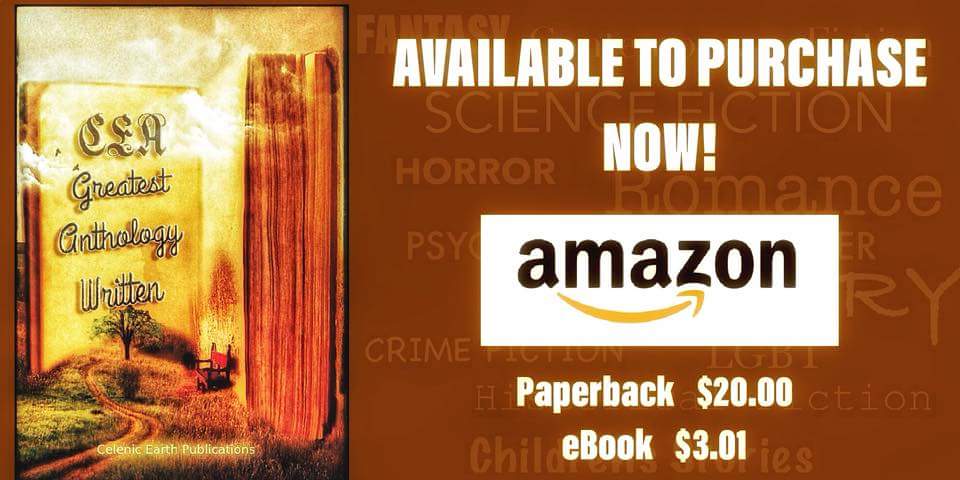

As noted in my earlier post today, the CEA Greatest Anthology Written is available to buy at Amazon. My contribution is a "Rabelaisian" piece called FANNY. You can read the opening scene below to get a sense if this is your kind of thing (and if it is, erm, you might wanna keep that secret).

FANNY (excerpt):

FANNY (excerpt):

Enormous Heizelfurst stood atop the desk, naked, pale and round as the whites of his bloodshot eyes. A champagne cork was lodged between a gap in his sparse teeth. Three encyclopedias balanced on his uneven balding head. In one apish palm rested a top hat, a fishbowl in the flue, the bowl full of matches. In the other hand he clutched a bouquet of carrots and lettuce. A bamboo tattooing needle sat behind his hairy right ear and behind his lopsided left one, a lady’s blue pen.

Desk, books, hat, fishbowl, pickles, needle, vegetables, matches, pen, cork and inappropriate nudity: None were his. He was like some god of misplaced things who had no followers because they couldn’t locate him.

Drapes curtained the bed, blankets draped the windows, the windows were raised and a sunshower sprinkled the woman in red kimono lying beneath. Her terra cotta lips opened flowerpot round and her silence was so beautiful and corpselike, Heizelfurst imagined the rain watered a rose in her throatbed.

A blizzard swept through his brain.

She gargled autumn cloud.

Heizelfurst shifted. The encyclopedias fell to the plush fuchsia rug (A, L, X-Y-Z). One opened to neat-bearded Lucretius the epicurean, who’d written in De Rerum Natura:

“We say a foul, filthy woman is ‘sweetly disordered,’

If she is green-eyed, we call her ‘my little Pallas’;

While a hulking giantess is ‘divinely statuesque.’

It would be tiresome to run through the whole list.”

These words came to Heizelfurst, and he remembered who he was suddenly as though the answer was simple as recalling the statement “One person is many people” is a logically valid conclusion to an argument whose premises are “Everybody loves someone” and “Nobody loves Heizelfurst.”

He was a philosopher who’d fallen from Academia’s peak like the stranger forever plummeting off the tarot card. Unlike that man, he seemed to lack significance. Every trip he’d made in public was a test run for this greater life-stumbling, all the humiliating laughter he’d endured at his pigeon-toed feet slipping on ice internalized, taken the form of that eye-piercing brain-blizzard.

He dropped misplaced things and they rattled, thumped and rolled, each distinct yet combined, a dissonant sound rainbow.

Outside a real one brightly frowned over Giftstadt.

The mouth closed.

The rain stopped.

“How are you, my little sweetly disordered, divinely statuesque Pallas?” he posed, failing to amuse, sitting on the desk.

A gurgled reply.

“Wet?”

Heizelfurst sighed, looked at his feet’s unfortunate curvature and belly’s unruly bulk, and thought about Plotinskshept’s third causality principle, i.e., the cause doesn’t produce the effect, but the effect reaches out for the cause from the future into the present, the two partners in an endless daisy chain of moments that are and are-to-be.

He slowly lowered his feet as though into a pool of freezing water—there was much winter about Heizelfurst today—then stepped over the chandelier to the woman.

“I—I can’t remember your name.”

She snarled.

No flower rose from that mouth, but an American

Don’t-Tread-On-Me snake:

“Fanny—“

“—My God.”

He was familiar with American English from an extended visit to the States begun in 1892, when he’d been living in Hamburg and used the cholera epidemic as an excuse to make the long-anticipated trip. The next year at Chicago’s World’s Fair he’d learned little about human progress but plenty vulgar slang. He switched to the colonial tongue:

“Yes, your fanny. Your fanny!”

“Yeah I’m Fanny.”

“No, your fanny, not you are Fanny. Don’t you remember? Last night I—“

“—I am Fanny, thanks very much. Fanny the Tranny, if you wanna know my whole name. Not that it’s a given name. More stolen.”

“Tranny? My God—Did we?”

Fanny peered between Heizelfurst's legs like a dying man searching for that tunnel of light he’d always heard about.

“Not that I recall. But then again you’re rather, well, lacking in certain qualities . . . I might not’ve felt it.”

This wasn’t the first time he’d heard this from a whore, and in less polite terms. He shrugged.

“It’s not important. But please let me see your, erm . . .”

“Ass?”

“Thank you, yes.”

“I’ve only been paid for one night.”

“It’s urgent.”

“All desire is.”

“You don’t understand.”

“I understand money.”

Heizelfurst’s trousers were neatly folded on a dresser. Beneath them was a book titled Mythological Dictionary that was, of course, an impossible thing.

He searched trouser pockets in vain for wallet or bankroll.

Fanny stood before the window framed in golden light, features blackened so he could be anybody. Heizelfurst knew the shadows hid wild eyes. In each, moss circles grew round abandoned well lips, black holes in which nothing respectable lived. But for every snake, insect and rodent, there’s someone whose passion is to study it, and Fanny’s eyes too must’ve had their admirers, experts, and cryptozoologists.

“Why am I here?” Heizelfurst asked.

“I was hired to bring you here, of course.”

“For what purpose?”

“Oh, fuck you.”

“There’s no need for that.”

“But you asked.”

“Who hired you?”

Fanny’s silence had a fetishistic intensity.

“I must see your behind. Please let me explain.

"Last night is hazy. Whatever I drank or ingested must’ve been potent. I don’t even wish to know what it was. I may not have a head to look at, but I’ve got one for ideas and puzzles. And I remember clearly I had you over my lap and I wrote, on your buttocks, an aphorism that was the culmination of all of my work for the last thirty years.

"I was struck as though with divine inspiration, immediately I knew I’d found IT . . . I give a lecture next week at the Giftstadt Academy of Sciences and Arts. It is my last—probably none will attend, but—if I were to present my new work there I could impart my thought to someone. It wouldn’t be in vain.”

“Was this before or after the spanking?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Actually it does. If you spanked me after the inscribing, well, the words could be indecipherable.”

"You’re right. I’m sure, though, I wouldn’t have struck those words—even if my mind was drug-fogged.”

“Your life’s work more important than my ass, then?”

“Well—“

“—Because that’s my life’s work, you know.”

“I didn’t mean—“

“—You don’t mean anything, Heizie. That’s why you’re here. But I play with ideas too. Maybe we can strike a deal.”

“Go on, please. Do you mind if I get dressed?”

“Mind? I demand it . . . ”

Desk, books, hat, fishbowl, pickles, needle, vegetables, matches, pen, cork and inappropriate nudity: None were his. He was like some god of misplaced things who had no followers because they couldn’t locate him.

Drapes curtained the bed, blankets draped the windows, the windows were raised and a sunshower sprinkled the woman in red kimono lying beneath. Her terra cotta lips opened flowerpot round and her silence was so beautiful and corpselike, Heizelfurst imagined the rain watered a rose in her throatbed.

A blizzard swept through his brain.

She gargled autumn cloud.

Heizelfurst shifted. The encyclopedias fell to the plush fuchsia rug (A, L, X-Y-Z). One opened to neat-bearded Lucretius the epicurean, who’d written in De Rerum Natura:

“We say a foul, filthy woman is ‘sweetly disordered,’

If she is green-eyed, we call her ‘my little Pallas’;

While a hulking giantess is ‘divinely statuesque.’

It would be tiresome to run through the whole list.”

These words came to Heizelfurst, and he remembered who he was suddenly as though the answer was simple as recalling the statement “One person is many people” is a logically valid conclusion to an argument whose premises are “Everybody loves someone” and “Nobody loves Heizelfurst.”

He was a philosopher who’d fallen from Academia’s peak like the stranger forever plummeting off the tarot card. Unlike that man, he seemed to lack significance. Every trip he’d made in public was a test run for this greater life-stumbling, all the humiliating laughter he’d endured at his pigeon-toed feet slipping on ice internalized, taken the form of that eye-piercing brain-blizzard.

He dropped misplaced things and they rattled, thumped and rolled, each distinct yet combined, a dissonant sound rainbow.

Outside a real one brightly frowned over Giftstadt.

The mouth closed.

The rain stopped.

“How are you, my little sweetly disordered, divinely statuesque Pallas?” he posed, failing to amuse, sitting on the desk.

A gurgled reply.

“Wet?”

Heizelfurst sighed, looked at his feet’s unfortunate curvature and belly’s unruly bulk, and thought about Plotinskshept’s third causality principle, i.e., the cause doesn’t produce the effect, but the effect reaches out for the cause from the future into the present, the two partners in an endless daisy chain of moments that are and are-to-be.

He slowly lowered his feet as though into a pool of freezing water—there was much winter about Heizelfurst today—then stepped over the chandelier to the woman.

“I—I can’t remember your name.”

She snarled.

No flower rose from that mouth, but an American

Don’t-Tread-On-Me snake:

“Fanny—“

“—My God.”

He was familiar with American English from an extended visit to the States begun in 1892, when he’d been living in Hamburg and used the cholera epidemic as an excuse to make the long-anticipated trip. The next year at Chicago’s World’s Fair he’d learned little about human progress but plenty vulgar slang. He switched to the colonial tongue:

“Yes, your fanny. Your fanny!”

“Yeah I’m Fanny.”

“No, your fanny, not you are Fanny. Don’t you remember? Last night I—“

“—I am Fanny, thanks very much. Fanny the Tranny, if you wanna know my whole name. Not that it’s a given name. More stolen.”

“Tranny? My God—Did we?”

Fanny peered between Heizelfurst's legs like a dying man searching for that tunnel of light he’d always heard about.

“Not that I recall. But then again you’re rather, well, lacking in certain qualities . . . I might not’ve felt it.”

This wasn’t the first time he’d heard this from a whore, and in less polite terms. He shrugged.

“It’s not important. But please let me see your, erm . . .”

“Ass?”

“Thank you, yes.”

“I’ve only been paid for one night.”

“It’s urgent.”

“All desire is.”

“You don’t understand.”

“I understand money.”

Heizelfurst’s trousers were neatly folded on a dresser. Beneath them was a book titled Mythological Dictionary that was, of course, an impossible thing.

He searched trouser pockets in vain for wallet or bankroll.

Fanny stood before the window framed in golden light, features blackened so he could be anybody. Heizelfurst knew the shadows hid wild eyes. In each, moss circles grew round abandoned well lips, black holes in which nothing respectable lived. But for every snake, insect and rodent, there’s someone whose passion is to study it, and Fanny’s eyes too must’ve had their admirers, experts, and cryptozoologists.

“Why am I here?” Heizelfurst asked.

“I was hired to bring you here, of course.”

“For what purpose?”

“Oh, fuck you.”

“There’s no need for that.”

“But you asked.”

“Who hired you?”

Fanny’s silence had a fetishistic intensity.

“I must see your behind. Please let me explain.

"Last night is hazy. Whatever I drank or ingested must’ve been potent. I don’t even wish to know what it was. I may not have a head to look at, but I’ve got one for ideas and puzzles. And I remember clearly I had you over my lap and I wrote, on your buttocks, an aphorism that was the culmination of all of my work for the last thirty years.

"I was struck as though with divine inspiration, immediately I knew I’d found IT . . . I give a lecture next week at the Giftstadt Academy of Sciences and Arts. It is my last—probably none will attend, but—if I were to present my new work there I could impart my thought to someone. It wouldn’t be in vain.”

“Was this before or after the spanking?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“Actually it does. If you spanked me after the inscribing, well, the words could be indecipherable.”

"You’re right. I’m sure, though, I wouldn’t have struck those words—even if my mind was drug-fogged.”

“Your life’s work more important than my ass, then?”

“Well—“

“—Because that’s my life’s work, you know.”

“I didn’t mean—“

“—You don’t mean anything, Heizie. That’s why you’re here. But I play with ideas too. Maybe we can strike a deal.”

“Go on, please. Do you mind if I get dressed?”

“Mind? I demand it . . . ”